|

The earliest known human remain discovered in modern-day Wales is a Neanderthal jawbone, found at the Bontnewydd Palaeolithic site in the valley of the River Elwy in North Wales, whose owner lived about 230,000 years ago in the Lower Palaeolithic period. The Red Lady of Paviland, a human skeleton dyed in red ochre, was discovered in 1823 in one of the Paviland limestone caves of the Gower Peninsula in Swansea, South Wales. Despite the name, the skeleton is that of a young man who lived about 33,000 years ago at the end of the Upper Paleolithic Period (old stone age).He is considered to be the oldest known ceremonial burial in Western Europe. The skeleton was found along with jewellery made from ivory and seashells and a mammoth's skull.

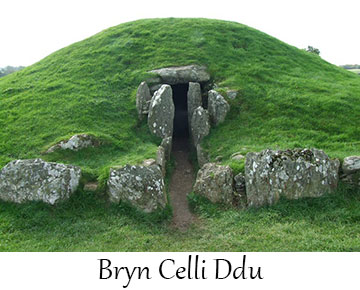

Following the last ice age, Wales became roughly the shape it is today by about 8000 BC and was inhabited by Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. The earliest farming communities are now believed to date from about 4000 BC, marking the beginning of the Neolithic period. This period saw the construction of many chambered tombs particularly dolmens or cromlechs. The most notable examples of megalithic tombs include Bryn Celli Ddu and Barclodiad y Gawres on Anglesey, Pentre Ifan in Pembrokeshire, and Tinkinswood Burial Chamber in the Vale of Glamorgan. was inhabited by Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. The earliest farming communities are now believed to date from about 4000 BC, marking the beginning of the Neolithic period. This period saw the construction of many chambered tombs particularly dolmens or cromlechs. The most notable examples of megalithic tombs include Bryn Celli Ddu and Barclodiad y Gawres on Anglesey, Pentre Ifan in Pembrokeshire, and Tinkinswood Burial Chamber in the Vale of Glamorgan.

Metal tools first appeared in Wales about 2500 BC, initially copper followed by bronze. The climate during the Early Bronze Age (c. 2500–1400 BC) is thought to have been warmer than at present, as there are many remains from this period in what are now bleak uplands. The Late Bronze Age (c. 1400–750 BC) saw the development of more advanced bronze implements. Much of the copper for the production of bronze probably came from the copper mine on the Great Orme, where prehistoric mining on a very large scale dates largely from the middle Bronze Age. Radiocarbon dating has shown the earliest hillforts in what would become Wales, to have been constructed during this period. Historian John Davies, theorises that a worsening climate after around 1250 BC – lower temperatures and heavier rainfall – required more productive land to be defended.

The earliest iron implement found in Wales is a sword from Llyn Fawr at the head of the Rhondda Valley, which is thought to date to about 600 BC. Hillforts continued to be built during the British Iron Age. Nearly 600 hillforts are in Wales, over 20% of those found in Britain, examples being Pen Dinas near Aberystwyth and Tre'r Ceiri on the Lleyn peninsula. A particularly significant find from this period was made in 1943 at Llyn Cerrig Bach on Anglesey, when the ground was being prepared for the construction of a Royal Air Force base. The cache included weapons, shields, chariots along with their fittings and harnesses, and slave chains and tools. Many had been deliberately broken and seem to have been votive offerings.

Until recently, the prehistory of Wales was portrayed as a series of successive migrations. The present tendency is to stress population continuity; the Encyclopedia of Wales suggests that Wales had received the greater part of its original stock of peoples by c.2000 BC. Recent studies in population genetics have argued for genetic continuity from the Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic or Neolithic eras. According to historian John Davies, the Brythonic languages spoken throughout Britain resulted from an indigenous "cumulative Celticity", rather than from migration.

|